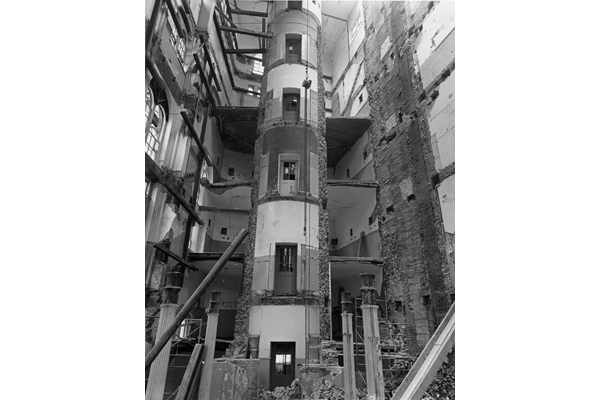

Construction Photo from the interior renovation of the Foundation Building, 1973 |

The interior renovation of the Foundation Building was formalized in large part due to the fact that the building was not to code. The large, open stairways at the south end, in addition to many antiquated features, deemed it a fire hazard and safety risk.

The renovation was initially intended to be a five-phase project constructed in defined areas while the building remained inhabited. After the first phase was completed in 1971 (the south stair and bathroom core), the costs of an ongoing multi-year project were weighed against the reality of a two to three year consolidated effort – a decision was made to vacate the entire building and complete the remaining four phases simultaneously. The institution compressed, and additional temporary space was rented on 14th Street.

Peter Bruder, the structural engineer for the project, designed exterior trusses that were placed at the four corners of the building to protect the façade against wind stresses and allow for demolition within the interior. An initial survey had revealed that the east to west bearing wall separating the southern portion of the building (what are now the lobby spaces) from the rest of the structure did not tie into the façade, and was not supported by adequate foundations. This condition was fortified in order to allow for the south end to be entirely gutted, leaving only the shaft of the round elevator in place.

In order to open up the lower floors as loft spaces, columns on the upper floors were suspended – literally floating without support. This required shoring from the sub-basement on up, in many instances activated by chases cut through the lower walls. It was only then that those load-bearing walls could be completely removed. Of the many tense moments during this process, one of the most was the truncation of the eastern diagonal truss at the second floor.

During construction, the building was once again restructured throughout. In translating the interior of the Foundation Building from a 19th Century innovation to a 20th Century work of modernist architecture, John Hejduk encased the work of Frederick Petersen and Leopold Eidlitz within the hand-troweled plaster finish work of the building. In her New York Times review of the completed work, Ada Louise Huxtable referred to the renovation as “an outstanding example of the real meaning of preservation at a time when the ‘recycling’ of older buildings of architectural merit is becoming increasingly common.”